“Man has a tremendous resistance to killing effectively with his bare hands. When man first picked up a club or a rock and killed his fellow man, he gained more than mechanical energy and mechanical leverage. He also gained psychological energy and psychological leverage that was every bit as necessary in the killing process”.

The act of killing another is no simple process, as Grossman (1995) points out. But as history has progressed, increasingly advanced forms of killing have been developed that remove the killer from the victim – both physically and morally. The ability to eliminate the moral bridge between killer and victim has been exploited to make the act of ending a life as simple as the press of a button. Now, with the development of drones and UAVs (Unmanned Air Vehicles), Mark Coeckelbergh (2013) believes the ultimate killing machine may have been developed, allowing the victim to become simply a point of data in the mind of the murderer, as he points out in the paper “Drones, information technology, and distance: mapping the moral epistemology of fighting”. However, unexpected moral and epistemological considerations have arisen as a result, which could help us consider more ethical approaches to warfare.

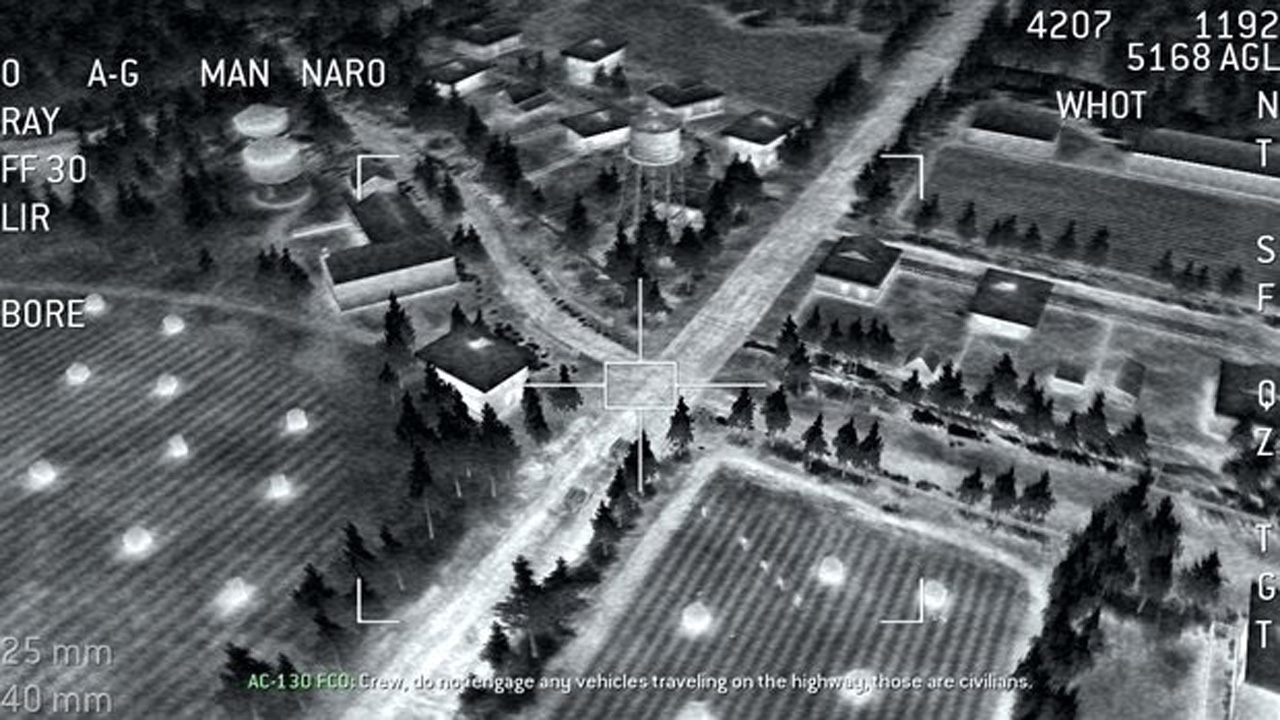

The term “screenfighter” applies to military personnel who engage in combat from behind a screen, rather than face-to-face on the battlefield. This achieves the aim of inflicting as much damage on the enemy as possible whilst reducing the risk to personnel, according to Valdes (2012). The operator of a drone could stroll into work one morning, kill a dozen or so people, and leave in the evening without ever being in any real danger. One wonders how a pilot can return to their family guilt-free. Drone warfare has been criticised for removing the moral responsibility from killing, by making the piloting of a war machine feel like playing a video game. The “cockpit” of the aircraft is a work station complete with large screens and joysticks. Footage that the pilot receives from the drone can be almost indistinguishable from a video game. This allows for the dehumanisation of the victim, removing the aspects of humanity from the target that might encourage the pilot to make more moral decisions. As Bruneau and Kteily (2017) point out, dehumanisation removes those moral and psychological inhibitions that make face-to-face killing so difficult. This may set a terrifying new precedent for the future of warfare, whereby all sense of personal responsibility of the pilot is removed, making them more susceptible to the will of authority without question, as Grossman (2001) recognises. The Milgram (1963) shock experiments showed the world the power of authority when participants willingly punished others using deadly amounts of electricity (or so they thought), under the belief they were absolved of responsibility by a higher authority. If drone warfare similarly allows for the removal of responsibility, it may mean pilots are more willing to accept their orders, even if they are highly unethical, such as the collateral killing of innocents.

from: https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/uxeNZ8RgrRFbPE8RQw4HJS.jpg

from: https://www.pond5.com/stock-footage/tag/military-drone/

Coeckelbergh believes the victim is in a sense “moral-epistemologically disarmed” before they are even killed. The entire socio-political context the pilot exists within encourages dehumanisation. Who is actually considered a target and for what reason is influenced largely by political actors, lawyers, heads of state etc., rather than being the concern of the pilot; all they have to do is follow orders. Ultimately, the person under the sights of the gun become little more than a bit of data. Every consequence that might hold a person back from the act of murder, the smell of blood, the sound of a person screaming in pain, is erased from the experience. One may even argue the pilot is somewhat ignorant of what they have just done. Coeckelbergh claims that by using a Heideggerian analysis, we can demonstrate that the opponent isn’t seen in a morally neutral way at first, but that before the pilot even has them in their sights, they are considered an enemy. Therefore it is not just that the physical distance creates a barrier that prevents empathy, but that the way drone warfare is conducted shapes the way the pilot thinks, making empathy near-impossible. From a psychological perspective this is very important to consider, as it implies that the ease of killing comes not from the inhibition of certain brain areas (e.g. areas related to empathy) or the faculties themselves (such as sympathy and empathy), but from the way the pilot’s view of themselves and the target person is heavily influenced. This understanding could help develop the nature of warfare in a more moral way, but would require a major change in the way information is shaped and distributed within the military system.

However, Coeckelbergh believes drone warfare isn’t as close to a video game as some think. Behind the screen remains a person who has the ability to reflect on their actions as a moral subject. In a study by Bullimer (2012), Colonel D. Scott Brenton, who flew a Reaper drone, supposedly said the “hair on his neck stands up” after every kill, suggesting an awareness of the act he is committing. After leaving his station, his adrenaline is still surging after squeezing the trigger, as drone warfare is not a “sanitised video game”. With advancements in surveillance technology, the pilot can now see a detailed image of their target’s face. Time is spent surveying them, potentially for months. This may re-bridge the moral gap between killer and victim. The pilot can once again relate to their opponent as a human being, and observe the consequences of their actions directly. Brenton recalls the differences he observed between piloting manned aircraft and drones. “I dropped bombs, hit my target load, but had no idea who I hit. [With drones], I can look at their faces… see these guys playing with their kids and wives… After the strike, I see the bodies being carried out of the house. I see the women weeping and in positions of mourning. That’s not PlayStation; that’s real.”

In conclusion, drone technology has arguably shifted the power dynamics of warfare, not only between killer and victim but also between pilot and commander. As leaked footage showing the obscene killing of Iraqi civilians by pilots of a US Apache helicopter, acting as if they are playing a video game, is still fresh in the minds of many, it is important to consider the conditions that lead up to the event. Such actions do not occur in a vacuum, but as part of the surrounding socio-political influences, as Coeckelbergh points out. Interviews with pilots demonstrate that they recognise the consequences of their actions. Therefore, discourse should focus not only on the role of the pilot, but also their place within the wider system that shapes the way they see the world. Only by acknowledging the effects of moral distancing and the dynamics of power in hierarchies can we hope to prevent unjust killings from happening again.

References

Bumiller, E. (2012). A day job waiting for a kill shot a world away. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes. com/2012/07/30/us/drone-pilots-waiting-for-a-kill-shot-7000-milesaway.html?pagewanted=all

Bruneau, E., & Kteily, N. (2017). The enemy as animal: Symmetric dehumanization during asymmetric warfare. PloS one, 12(7).

Coeckelbergh, M. (2013). Drones, information technology, and distance: mapping the moral epistemology of remote fighting. Ethics and information technology, 15(2), 87-98.

Grossman, D. (1995). On killing: The psychological cost of learning to kill in war and society. New York/Boston/London: Little, Brown & Company. revised edition 2009.

Grossman, D. (2001). On killing. II: The psychological cost of learning to kill. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 3(3), 137–144.

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. The Journal of abnormal and social psychology, 67(4), 371.

Valdes, R. (2012). How the predator UAV works. HowStuffWorks. Retrieved from http://science.howstuffworks.com/predator4. htm/printable.